Storytelling with Talking Animals

From the start, I knew Żużel and the Fox was going to be anthropomorphic. I wanted to tell this story with talking animals. But that meant I had to think about how to anthropomorphize them. To what extent should they be human? To what extent animal?

I thought the answer should carry some meaning. In other words, anthropomorphism should help tell the story.

So I started thinking about the character design in some of my favorite anthro movies and comics. Disney has shown us a range of anthropomorphism in its characters. On the more human side, there’s Robin Hood (1973). On the more animal side, there’s The Jungle Book (1967) and 101 Dalmatians (1961). The comic book Blacksad, illustrated by an ex-Disney animator, opts for a more-human physiology. And Shane-Michael Vidaurri’s Iron: or, the War After uses totally-human bodies with animal heads. Maus is also an important touchstone: human bodies, but a very cartoony style.

I noticed some general rules. In worlds where animals interact with humans, they keep their animal shape. In worlds without humans, the animals usually end up somewhere in the middle. A kind of half-and-half anthropomorphism. In worlds where anthro characters interact with animals, they tend to be more completely human. This all made sense: character design, like any kind of design, is about making distinctions that aid comprehension.

There’s a fun moment in Fantasia 2000 when Donald Duck, an anthro duck, is checking off animals entering Noah’s ark. Two non-anthro mallard ducks waddle by, and Donald does a double take. While I find this hilarious, I wanted to avoid that kind of self-conscious awkwardness in my graphic novel.

Two Rules for Anthropomorphism in Żużel and the Fox

In the end, I decided that in the world of Żużel and the Fox, physiology had to be liquid and pliable. This means characters can show various degrees of anthropomorphism when compared to each other. Also, their physiology can change over time.

Now, that could result in very incoherent character design. Hybrid creatures who don’t belong in the same world. So here’s the solution I came up with: two general rules.

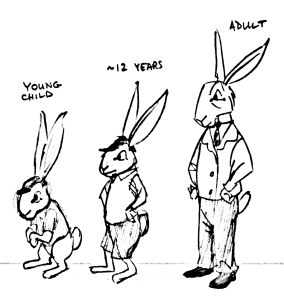

First, children are generally more animal, and become more human as they age. So, for example, Szybki, a street urchin, is structured more like a rabbit than a human. Zittern, a German cop, is structured more like a human than a dog. As we age, we gain more self-control, and are more likely to follow social conventions; conversely, we lose our freedom and become more self-conscious. So, the age-rule can help emphasize these ideas when distinguishing characters. It can also help us relate with the changing issues characters face as they age.

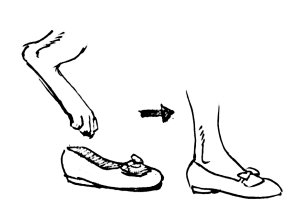

Second, the more clothes a character wears, the more human they become. This flexibility is not constrained to a character’s age, and can cause immediate and extreme changes. Thus an adult character with a very human build can, if stripped of clothing, become totally animal in build. They say “the clothes make the man.” And there are a number of storytelling tropes where we associate dressing with pride and stripping with shame.

Do the Characters Know?

Now, this fluidity of form could create problems–are the characters aware of it, or not? I decided the characters do not perceive changes in physiology as such. Say Żużel, a kitten, is forced to put on a pair of shoes. She would view the loss of her feline leg-structure as a loss of freedom of movement, a loss of agility. Say an adult is shame-stripped, and thus transformed into an animal. This would be seen as a loss of dignity or humanity.

In those examples, the purpose of fluid anthropomorphism, from a storytelling perspective, hopefully becomes more apparent. The character’s physical appearance becomes a visual device to resonate with the thematic questions in the story.

- In what ways to manipulation, racism, and sadism dehumanize both the victims and the perpetrators?

- In what ways do the trappings of civilization limit us? In what ways do they make us more human?

- In what ways do some people use social conventions to hide their barbarity?

- And how do the cultural assumptions and primal instincts for parenthood conflict?

These questions are important to me. And if a talking-animal comic book like Żużel and the Fox tries to answer them, then maybe it is a story worth telling.

Further Reading

Here is a more recent post where I use a brief animation to analyze the problem of digitigrade characters who walk upright.

Very helpful. Thanks for sharing

Thoughtful analysis of what for many anthro artists is a gut decision. I learned some new things, thank you.