Comics Translation: Not Just about Words

I’d be lying if I said I was surprised, taken aback, befuddled. I knew well that creating a Polish eBook of the first 50 comics would pose many challenges. That is, I knew it theoretically. But there were some surprises when it came to what exactly the perils of comics translation were.

Turns out differences in culture and grammar are just the tip of the iceberg. Translating a comic isn’t just about words; its about the interlocking relationships between the words and pictures. And it can be quite a wrestling match.

Culture and Politics

My translator expressed concern that the subject material may be objectionable to Polish readers, especially older ones. As a result we made some small edits, and avoided any statements about the Second Polish Republic, or references to Józef Piłsudski. Anything that could be construed as political in intent was expunged. Although these deletions were voluntary, I came to appreciate, more personally, the freedom of speech we enjoy in this country. Granted, I’m not creating a version of my comics for Polish readers in say, 1960–the book would never make it past the Polish border.

These edits, in the end, were not about politics in the usual sense.

Working with my translator, I saw the whole project in a new light. I was a bit ashamed that I hadn’t considered the possibility that jokey, absurdist comics about the Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza could be offensive. Indeed, she reminded me that most of the KOP were murdered at Katyń, or ended up in labor camps after the Soviets took them prisoner in 1939. While to my mind, the comics do these soldiers some small honor by reminding the world that they existed, and that they were more than just victims of war–I realize now that I do tread a fine line.

Lost Jokes and Grammar

My translator and I went back and forth trying to sort out a few of the jokes. But as I started compositing the Polish word bubbles, new questions arose. I am lucky to have a couple friends online who have generously offered to answer those questions. But we usually have to settle for a compromise.

My translator did a great job; she was professional, friendly, and timely. But there are some jokes that were just impossible for her to translate. And they weren’t the ones I expected. For example, I thought the “fire in the hole” pun would be impossible. Not so; apparently the phrase has been calqued into Polish. On the other hand, it surprised me to learn the “flapper” concept didn’t exist in Poland.

A lot of these cultural differences were easy to work around. However, some jokes seem just downright untranslatable. I’m still working out with a friend how to have Kasia correct Kowak’s speech and maintain dramatic irony. We’re scratching our heads.

Polish is a language with a beautifully complex grammar. What I didn’t realize is how this affects the notion of a speaker having “bad grammar.” At least among the Polish-speakers I’ve consulted. For instance, can one say “ain’t” or “gotta” or “should of” in Polish? There doesn’t seem to be anything close to an analogue to these popular substandard English phrases.

One fascinating notion I’ve developed is that in Polish, grammar–or I should say, morphology–seems to spill into rhetoric. Polish grammar seems to control various aspects of what, in English, we’d call cohesion. As a teacher I’m always pointing out the line between grammar and cohesion to my students. A sentence can be grammatically correct, no errors–but have a confusing, misleading, or vague connection to the sentences around it.

My translator and my Polish-speaking friends are always asking for more context. That makes sense; there are many reasons why you can’t translate a sentence in isolation. But the reasons they cite are always morphological. Let me try to explain. Imagine that in an English paragraph, you are talking about two males. It’s easy to get your pronouns tangled–which male does this “he” refer to? You sometimes have to really twist a sentence to avoid ambiguity. So, we use syntax–word order–to keep it cohesive. As far as I can tell, Polish seems to use grammar in the same way. But I may be completely wrong.

Bubble Trouble

Polish can be very elegant in some ways, but in others, it is clunky. I’ve gained a new appreciation for how effortlessly English embeds clauses:

I think he said she thought I should.

Polish doesn’t seem to enjoy doing that sort of thing. And, like other languages I’ve encountered, Polish marks off subordinate clauses with commas. For illustration, here’s what that sentence above might look like if English followed Polish rules:

I think, that he said, that she thought, that I should.

I know I’m oversimplifying everything. But this is my basic understanding of why a number of my word bubbles ended up so much longer. In the comics medium, every square milimeter counts, and is accounted for.

I also ran into trouble with some long words and “non-breaking spaces.” Fifty-cent words like nieprawdopodobny demand a horizontal bubble–which can be an issue in a narrow panel. And Polish typesetting forbids the separation of one-letter words from the word that follows. Phrases like w dziurze can’t be broken up. This may seem like a minor thing–but believe me, it gummed up its fair share of word bubbles.

Word bubble layout sometimes feels like a game. Write and rewrite your dialogue so it fits nicely into a diamond shape. Keep your white space consistent and even–avoid big pockets. But with those long words and non-breaking spaces, sometimes you just have to throw in the towel.

Layout Adjustments

I am very thankful I’ve been working in the digital medium. Not just because of our old friend CTRL+Z. I’ve spent so many hours resizing and moving word bubbles to maintain a readable layout. And this whole process would be impossible if I didn’t have art and bubbles on separate layers.

I also have thanked my past self for another reason. Many times, while creating background art, I’ve thought, Why waste the time on art that will mostly never be seen? That’s right–a good portion of the art I create for each comic doesn’t end up getting seen. There’s a full background image behind the figures and word bubbles. I do this so I can recycle the backgrounds in new comics. And because anyway, as artwork, the backgrounds come out better, more cohesive, if I draw and color them as a complete image–not just scraps around the periphery of a foreground figure.

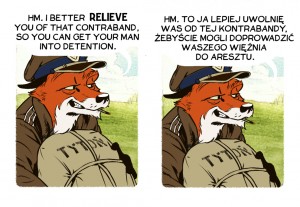

During the process of translating the comics, I’ve had to make all kinds of changes. Changes that wouldn’t be possible if the artwork were all on one layer. For example, in this panel:

I had to make room for more words. I had to extend the bubble. I had to lower and slightly shrink Rudek. I had to move everything again, because in the process I created a tangent with his muzzle and the hill in the background. Finally, I got the panel to the right. I wouldn’t have been able to do any of that without layers.

I had to make room for more words. I had to extend the bubble. I had to lower and slightly shrink Rudek. I had to move everything again, because in the process I created a tangent with his muzzle and the hill in the background. Finally, I got the panel to the right. I wouldn’t have been able to do any of that without layers.

Heh, this is certainly relatable.

Most difficult thing about translating (in my experience, amateur translation from English to Greek) is definitely the jokes, and especially the wordplay.

Yes, a lot of phrases are shared across a ton of languages, but most are not. Even if a joke is technically “translatable”, if its english origin is blatant, then you are going to have to revise. Some jokes are simply untranslatable, and have to be replaced with others which are in a similar tone. Managing to do convincing, “smooth” wordplay accross two languages is really, really challenging.

“absurdist comics about the Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza could be offensive”

I don’t know much about Polish culture, but this surprises me. I can’t imagine a military comedy not satirizing the semi-absurd nature of an army.

While I am sure it was probably an exaggeration on the translator’s part, there is a very fine line between treading lightly and self censorship.

Czech is physically shorter, but even more complex than Polish (there are now only 3 Czech grammars, spoken, formal, and written – it used to be worse, and fuller of Germanisms!). Count yourself lucky with these problems, my friend.

Also, your observations about structure and class connotations seem spot on to me.

I’d add that one area where English is NOT far more flexible and subtle than most languages, and particularly Polish, is relational terms. Words for others signal so much more about a relationship in Polish, and it changes based on context, that an English speaker’s head can explode. I really admire you for working through this. For example, many of us are familiar with English’s tendency to use one word many ways, as in “I love my child.” “I love the Lord.” and “I love tomatoes.” That’s profoundly weird, because we’re talking about really different concepts here (C.S. Lewis’ The Four Loves is a good introduction to the complexity of the word), but even that one word is unsubtle comapred to relational Polish because of name forms.

God speed. You’re doing good work.